A Brief History Of French Fashion

Le Magnifique: we take a brief look at the French fashion houses that defined the 20th century up until the 1960s. From Poiret and Chanel to Dior...

Le Magnifique: we take a brief look at the French fashion houses that defined the 20th century up until the 1960s. From Poiret and Chanel to Dior...

In the late 19th century, a working class boy from Paris took something insignificant and made it magnificent. Apprenticed to an umbrella maker, he collected scraps of silk left on the cutting room floor and fashioned them into a dress for his sister’s doll. The boy was Paul Poiret and over the next century he would help change Parisian fashion forever.

France's bodice-ditching flapper revolution in the early 20th century - and the history of the modern dress - doesn’t start with Coco Chanel. Our story begins in the early 1900s with Poiret in an exotic wonderland filled with luxurious capes, daring kimono jackets, crushed velvet draping and harem pants…

In 1906, Poiret did something shocking. He rejected the corset and introduced a new concept to women's fashion: freedom of movement. Not everyone was pleased with his revolutionary designs. Greeted with a kimono-cut cloak made out of black wool in 1901, the Russian Princess Bariatinsky cried out “what a horror!” Luckily the masses didn’t quite agree and in 1903 Poiret established his own house of couture. Just seven years later he would be known as “The King of Fashion” by Americans. In Paris? Just two words: “Le Magnifique”.

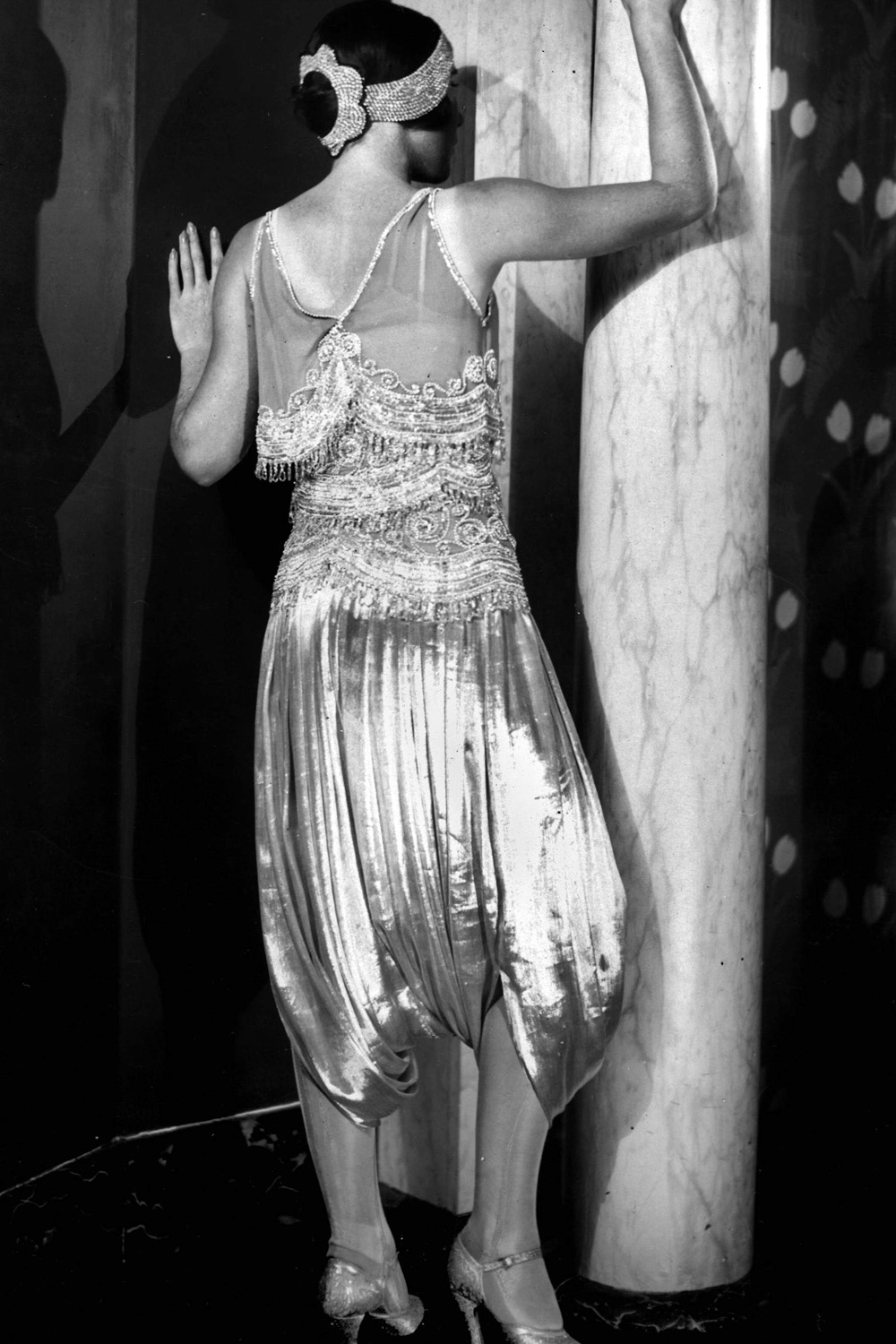

Looking at Poiret’s sumptuous dress designs it's not hard to understand why. Evoking the oriental spirit of Diaghilev's Ballet Russes, his harem pants and sultana skirts were lapped up by eager fashionistas with equally eager purses. Poiret’s naturalistic touch traced the flowing curves of the Art Nouveau period and you can see it in each cloth-fold. Fabric drapes ripple like water. Beauty, for Poiret, was in the finer details such as the small of a back - far more erotic than a heaving, bodiced chest. For the very first time, a woman’s body wasn’t fetishised for the male gaze and it wasn’t constricted. Petticoats and corsets were out. Women could breathe again.

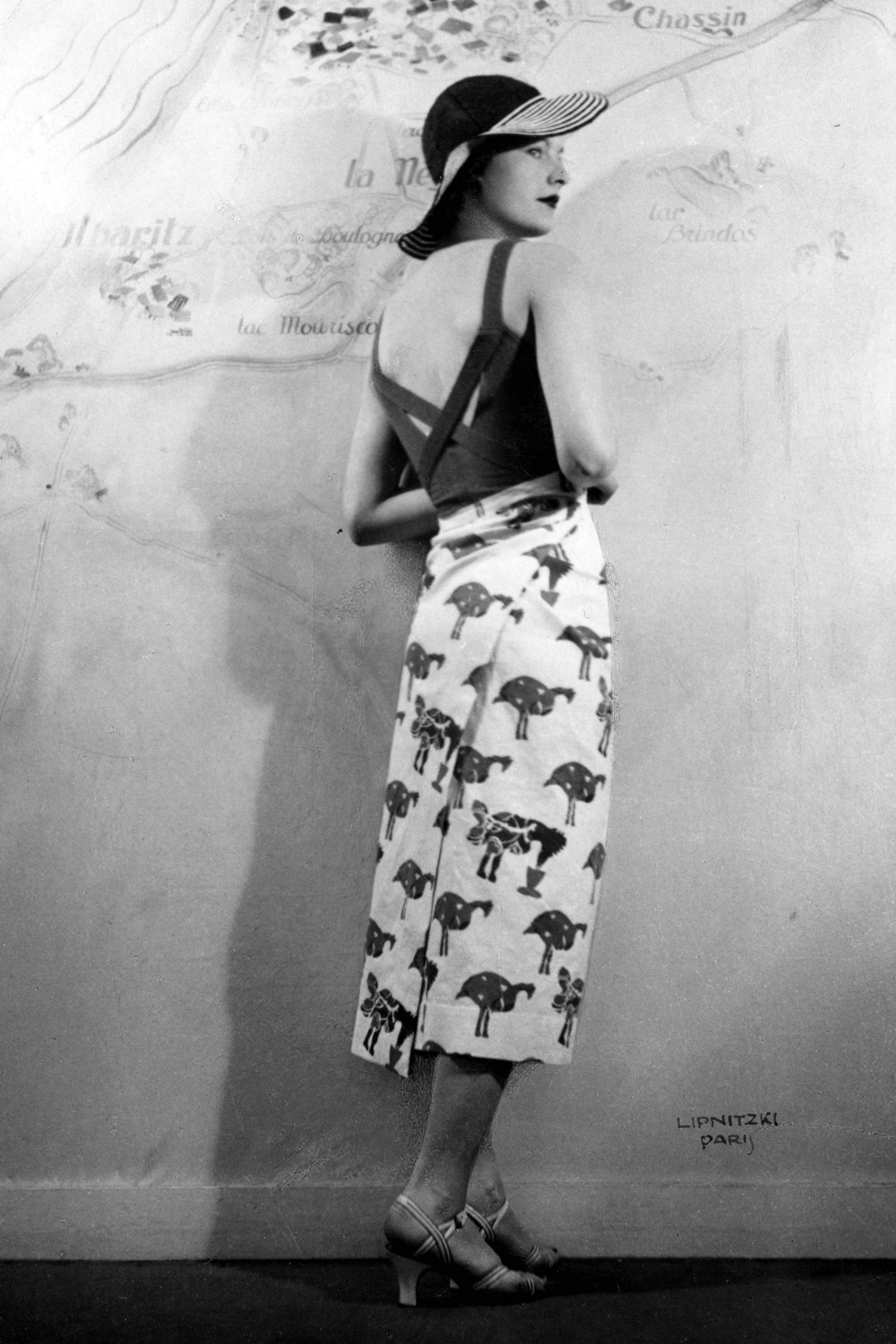

With the encouragement of Poiret himself, Elsa Schiaparelli - an Italian in Paris - came to the fashion-fore during the interwar years. Heavily influenced by the Dada movement, Schiaparelli embraced Poiret's corset abandonment adding her own impulsive style. It may come as a shock to learn that Elsa had no formal training in technical design. The freedom of movement that Poiret masterminded would come to define Schiaparelli's personal approach to her work: she would drape fabric directly on the body and pin accordingly.

Schiaparelli pioneered many firsts during her career: she was one of the first fashion designers to develop the wrap dress in 1930, four decades before Diane von Fürstenberg in the 1970s. She was also the first to elevate zippers, transforming them into a quirky, visible embellishment - decorative, not just practical. But what we love most about Schiaparelli was her sense of fun. During Prohibition in the US she famously (and mischievously) fashioned a "speakeasy dress" with a hidden flask pocket. Zelda Fitzgerald must have been first in the queue.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

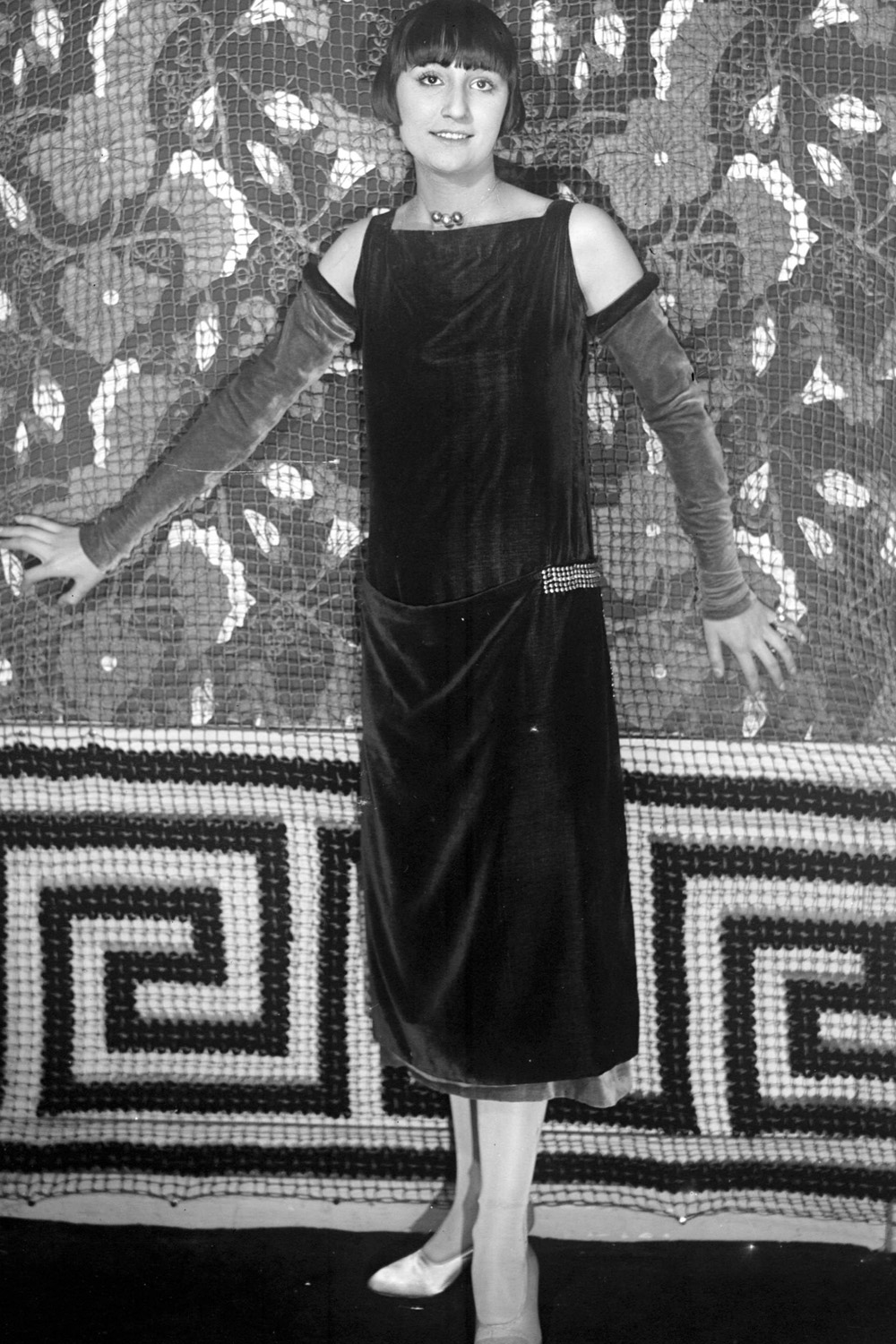

Coco Chanel once said: “Look for the woman in the dress. If there is no woman there is no dress.” Sounds simple, doesn’t it? But if you look back over the centuries, dresses were made irrespective of the women who wore them. In the 1920s everything changed. Inspired by Poiret, Chanel took ownership of the new liberated silhouette and ran with it. In the aftermath of WW1 all naivety was lost and sexual ambiguity was embraced: hobble skirts and wide-brimmed hats were slowing women down. Coco welcomed in the leg-flicking flapper age with her shortened skirts, cropped hair, Breton stripes and sailor pants.

Her second boutique opened in 1915 in Biarritz opposite a casino, selling modern designs made from humble fabrics to aristocratic customers. In the early 1900s, jersey was a controversial fabric that was used for one purpose only. As current Chanel designer, Karl Largerfeld, explained to Vogue: “Jersey was men’s underwear material and it was much more shocking in those days because women weren't supposed to know that men wore underwear. And Chanel made dresses from them.” Revolution was in the air.

Chanel’s powerful influence continued well into the 1930s with American Vogue likening her LBD (little black dress) to the mass popularity of the Ford motorcar in 1926. It wouldn’t be until the early 1950s that Coco would strike gold again with her iconic Chanel jacket. Its cropped length and boxed lines threw down the gauntlet, ready for combat. Her adversary? Christian Dior.

In 1947, Dior launched his “New Look” at his salon at 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris. If Chanel’s designs were all about freeing women from gender constraints, Dior’s shapely silhouette keenly cinched women back into familiar feminine lines after WW2. Full skirts, nipped in waists and brimmed hats were back. Corsets and petticoats made a triumphant return. “I have designed flower women”, Dior famously declared at the time. “Mr Dior, we abhor dresses to the floor,” came the sharp response from some angry women with placards. These protests wouldn’t prevent Dior’s silhouette dominating the 1950s, however.

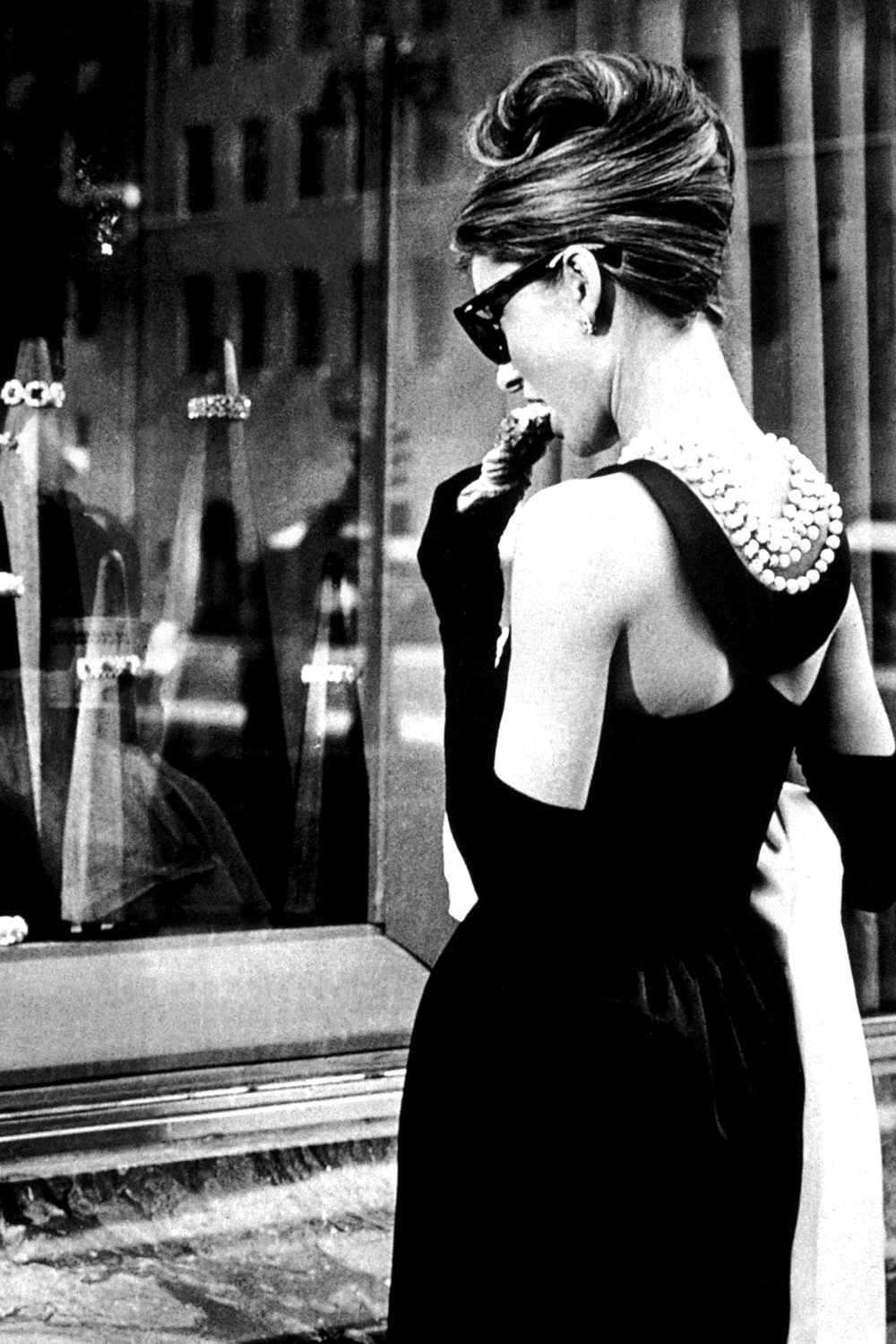

Which brings us to a colleague of Dior’s. In 1953, Audrey Hepburn and Givenchy met on the set of Sabrina. The rest, as they say, made history. Givenchy re-imagined Chanel’s LBD for a new audience with the help of Hepburn, a pair of sunglasses…and a little-known film called Breakfast at Tiffany’s. “His are the only clothes in which I am myself. He is far more than a couturier, he is a creator of personality,' Givenchy's muse would later say.

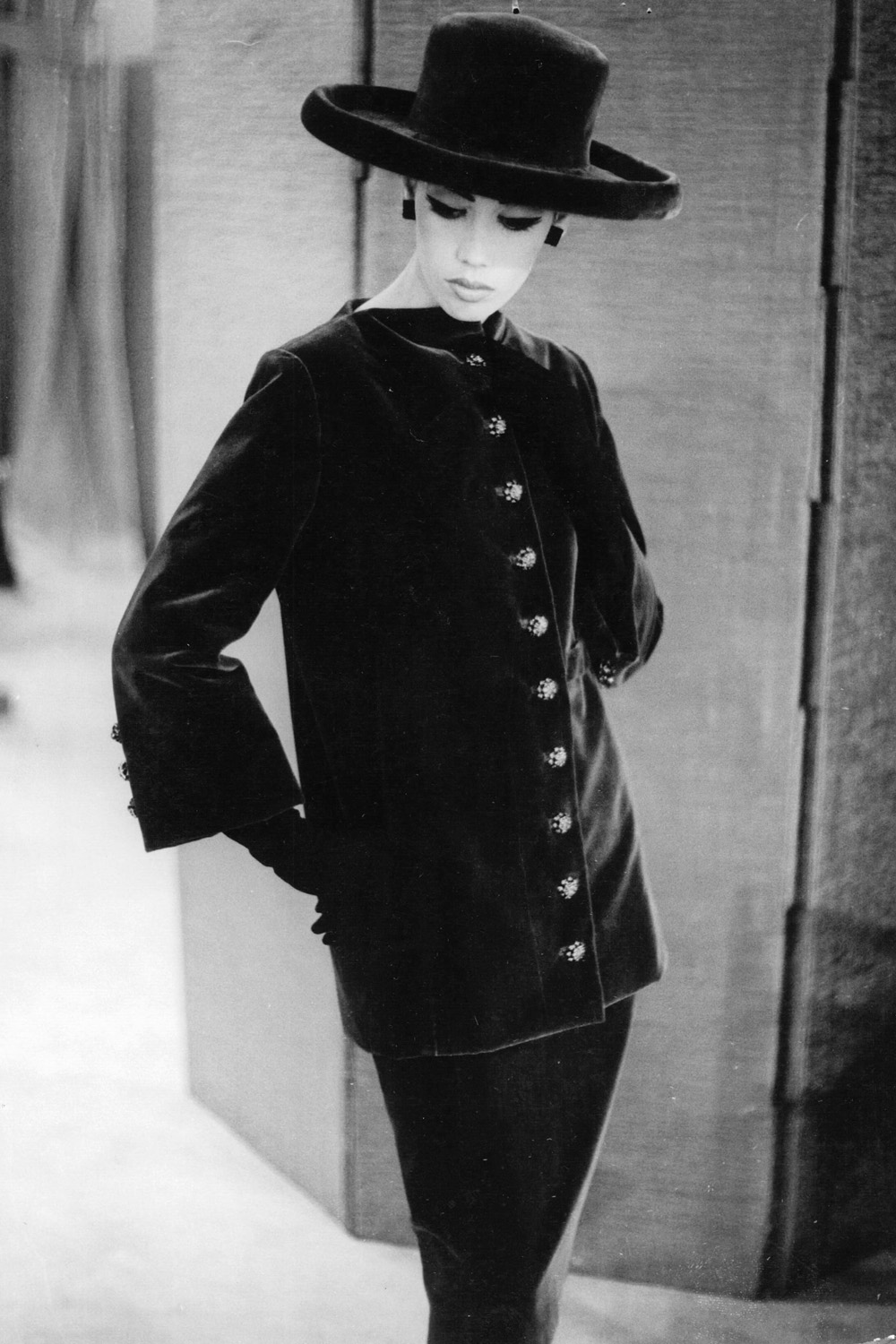

Where Hepburn ventured, the rest of Hollywood's A-list followed, from Elizabeth Taylor to Grace Kelly. In 1957 Givenchy introduced his inconic design: the "sack" silhouette. Although its name sounds underwhelming, the product itself revolutionised the female figure, enveloping the wearer and subverting traditional femininity once again. Her body underneath? A mystery. Hemlines were raised and a new decade was beckoning...

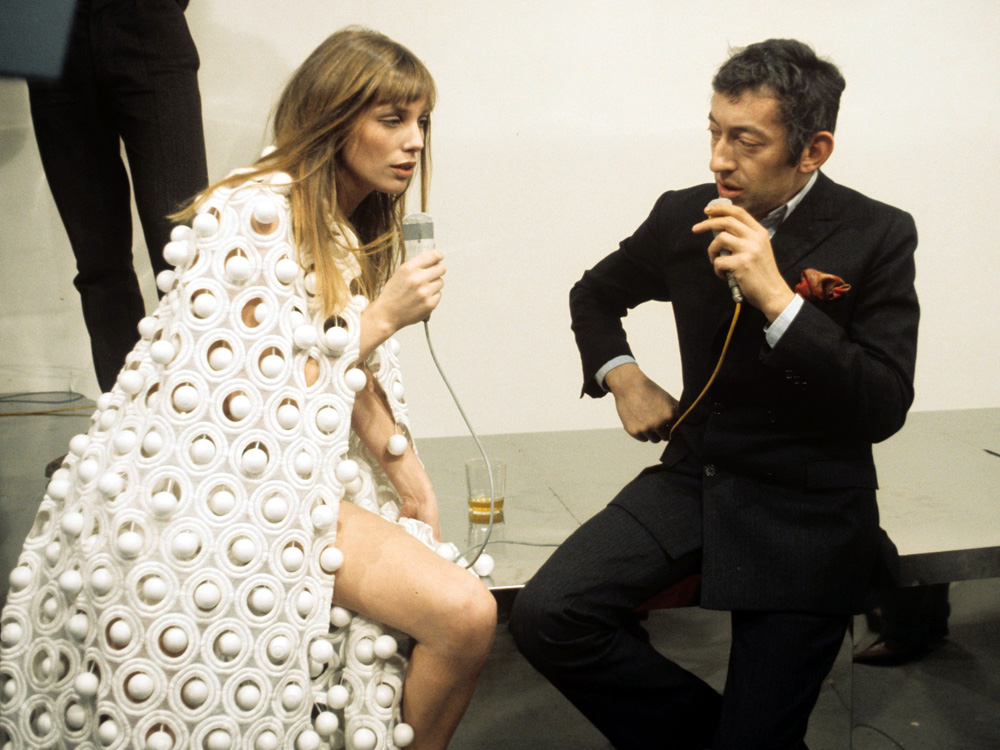

Fast-forward to the 1960s, London was swinging and France wasn’t far behind. High fashion was yesterday's news: the yé-yé movement was in full-flow and it soon made sexily dishevelled stars out of the likes of Serge Gainsbourg and Françoise Hardy. It also created an eternal style couple out of Serge and his wife, Jane Birkin. Mini skirts, bare feet and picnic baskets ruled the nightclubs: Beatnik was the word-du-jour.

In 1966 Yves Saint Laurent responded to the change in scene with a “ready to wear” line and an iconic look: the classic tuxedo suit for women. Just a year earlier, in 1965, he unveiled his Mondrian Collection. These six cocktail dresses, inspired by the work of the paintings of Mondrian, are now considered art themselves.

Paris may still be considered the fashion capital of the world, but French fashion would never shine as brightly as it did in the '60s and for one good reason: in subsequent years, global cities such as London, New York and Tokyo levelled the playing field. But you know what Sabrina said? Paris is always a good idea. In the heady days of loose skirts and rouged knees it wasn't just good. Paris was free. It was magnifique.

The leading destination for fashion, beauty, shopping and finger-on-the-pulse views on the latest issues. Marie Claire's travel content helps you delight in discovering new destinations around the globe, offering a unique – and sometimes unchartered – travel experience. From new hotel openings to the destinations tipped to take over our travel calendars, this iconic name has it covered.